Silver Stories

Church Silver of the Theodore Parker Unitarian Universalist Church

West Roxbury, Massachusetts

by Dr. Mary Ann Millsap

May 6, 2012

Introduction

Three hundred years ago, when our current Theodore Parker Church first gathered as the Second Parish Church of Roxbury, we met in a humble meeting house. Five years ago, I learned as an “oh, by the way” that we had church silver stored at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston. It seemed so incongruous to have silver in that rustic meeting house. .. but it’s true.

I saw our 13 pieces of silver in spring 2008, when we went to the MFA to have the silver appraised. I read the engravings of who had gifted it and when, and scanned through the massive catalog of the 1911 MFA exhibit of colonial church silver. This is how it looks today.

The silver is beautiful. The appraiser (Alexander Goriansky) thought we have a “fine collection” and that our “collection of tankards by five (and presumably six) different makers piques interest for comparative study.”

So of course, it piqued my curiosity to find out more. Why silver? How was it used in church settings? Who gave it? Who made it?

Why Silver?

Silver was the only reliable currency in colonial times. With multiple currencies in use, and with the continuing depreciation of the Massachusetts paper currency (and concomitant rise in the price of silver), silver was of great value. Silversmiths were the bankers for those fortunate enough to have silver coins. To keep the coins from being stolen, silversmiths melted them down, made household items from them (such as tankards, beakers, and spoons), stamped their own marks on the pieces, and often also stamped on the owner’s monogram or crest. This domestic silver was then often given to the church for use in church rituals.

As you can see from our silver, it is simple in design. It is also substantial in weight. The tankards, for example, are about 8-9 inches high and weigh about 30 oz., while the basin is about 11 inches in diameter and weighs 24 oz . According to R.T. Haines Halsey, a New York expert on old silver noted in 1911: “The early American silver, as in the case of our early architecture and furniture, is thoroughly characteristic of the taste and life of the period in America…..It reflects the classic mental attitude of the people. Social conditions here warranted no attempt to imitate the magnificent baronial silver made in England.”

Who Were These People? Where Did They Come From? The Great Migration

The story of our silver begins not in 1712 when the Second Parish of Roxbury first gathered, but with the Great Migration from 1630 to 1641 when over 14,000 men, women and children sailed to Massachusetts from England. Many came as families, including intact church communities. In Roxbury, for example, some 59 people followed their English minister, John Eliot, to found our parent church, the First Church of Roxbury (near Roxbury Crossing). In addition to ministering to his flock, John Eliot also learned the language of the native Indians, translated the entire bible into their language, and became known as “The Apostle to the Indians.” He also started the first school — Roxbury Latin [now located on Centre Street, West Roxbury, next door to St. Theresa’s Catholic Church].

Those who came in the Great Migration with Eliot were, as one early settler reported:

“…people of substance, many of them farmers, none being ‘of the poorer sort.’ They struck root in the soil immediately and were enterprising, industrious, and frugal.”

Among the early settlers, a few were investors in the colony, including the Welds, so were given larger tracts of land. The Weld family’s 300 acres encompassed today’s Arnold Arboretum and beyond. Most settlers were given 30 to 40 acres – some pasture, some marsh land for hay. Most were farmers or in farm-supporting fields – gunsmiths, blacksmiths, millers. Once settled in Roxbury, they stayed generation after generation. Within Roxbury’s 16 square miles, families had lots of growing room. Families were large – 5, 7, 9, 11 children. For the most part, it was the descendants (typically the grandchildren) of these early Puritans who started the Second Parish Church in 1712, and their descendants who became the silver donors.

Before I talk about the individual donors, I want to talk briefly about the everyday world of the Puritans, including their church services and how they used silver vessels.

What Did They Create? What Were Their Church Practices?

While the Massachusetts Bay Colony was intended as a business venture, the colony was a refuge for the Puritans who felt that this was their chance to build a completely new community with new institutions.

The Puritans had left their homes in England to start a new community — in a dangerous place. The weather was bitterly cold, the land was not particularly fertile, they had few resources, and they faced both disease and Indians already living on the land they wanted. Of the 700 people who arrived in 1630 with John Winthrop, the colony’s first governor, up to 200 people died within the first six months. To survive under such hostile conditions, the Puritans banded very closely together. Social cohesion and mutual support were their guiding principles. Dissent, especially dissent that challenged church theology, as was the case with both Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson, was not tolerated.

The political, religious, and educational functions of the colony were completely intertwined. The Puritans created a theocracy, with each individual church as a self-governing body within it. The General Court of Massachusetts, for example, set the catchment area of a church (that is, it defined the “parish” boundaries), taxed each head of a family its proportion to pay for the church, set the amount of the minister’s annual stipend, and required each town to have at least one (often more) tythingman whose job included ensuring that people came to church, stayed awake, and did not disrupt services. The meeting house was used not only for the worship of God but also for town meetings.

Within each town, the Puritan settlers built their meetinghouse as soon as possible. The first meetinghouses were rude structures – square log-houses with clay-filled chinks, surmounted by steep roofs thatched with long straw or grass and often with only the beaten earth for a floor. The seats were long, narrow, uncomfortable benches, made of rough-hewn planks. The men sat on one side, women and girls sat on the other, and boys sat in the balcony or on stairs, with the tythingman appointed to watch over them and control them. Although many churches made do with one or two tythingmen, the Second Parish under its second minister, Nathaniel Walter, appointed four tythingmen, a number which was soon increased to six. It does make you wonder about how rowdy our early congregants were. Black slaves were often in domestic service to the more wealthy Roxbury families. The blacks had seats by themselves. The black women were all seated on a long bench labeled “BW” and the black men in one labeled “BM”.

The service started around 9:00 in the morning. Sermons were often two or three hours. There was a break for the noon meal, and another afternoon session for 2-3 hours for sermons and prayers. For the noon-meal, congregants went to the “noon house,” a rough building with a stone chimney at one end where congregants could warm up and eat the cold food they had brought with them.

Celebrating the Sacraments

For church rituals, the Puritans retained only those customs and practices that the New Testament described – baptism and communion – and avoided using any trappings of the high church (Anglican or Catholic).

Baptism

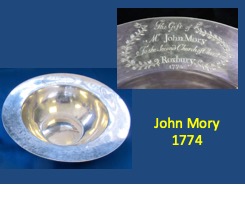

The Puritans practiced infant baptism. Children were always carried to the meeting house for baptism the first Sunday after birth, even in the most bitter weather. In the first year of the Second Parish Church, Rev. Ebenezer Thayer performed 11 baptisms; in the second year, he performed 22. Unlike the Anglicans, the Puritans used a bowl instead of baptismal fonts. In the early days of the church, any domestic vessel of wood, pewter, pottery or glass was requisitioned for use in the rite of baptism. Silver basins were introduced in the 1700s and were a sign of the growing prosperity of the colonists. This is our silver baptismal basin, gifted to the church in 1774. Later on, we’ll talk about its donor.

Communion

The Puritans held a monthly communion service to celebrate the sacrament of the Lord’s supper. To have their service more closely resemble the last supper Jesus shared with his disciples, they used multiple vessels associated with convivial gatherings, rather than a single ornate chalice.

From what I’ve been able to find, congregants celebrated communion in one of two ways. In one, people walked up to a communion table where deacons extended sacramental bread and wine through a variety of vessels, some of higher status than others. In this model, prominent people received the bread and wine first. We don’t know about the Second Parish, but – at another church — Judge Samuel Sewell who kept an extensive diary during this time admitted feeling “flushed” and some “humiliation” when he received the humbler tankard rather than the standing cup in his church. In the other form, people remained in their pews or on benches with communion plates and tankards (or beakers) passed from person to person. The New England churches that adopted this latter form of communion used matching vessels to eliminate social distinctions and to emphasize the special spiritual equality existing among God’s elect.

Our communion service is a collection of tankards, similar but not identical tankards. While no doubt there were social distinctions among the congregants, the tankard communion reinforced the sense of community and common purpose.

In the early colonial period, the vessels holding the sacramental wine could be made of pewter, wood, or pottery –whatever was available – but quickly shifted to silver virtually everywhere. The use of silver was incredibly wide-spread. There were 2,000 pieces of New England colonial church silver in the 1911 MFA exhibit.

What makes the donation of silver so remarkable is that silver was real money – it was the only universally accepted medium of exchange in the colonies. The decision to reserve a substantial amount of this precious and highly useful metal for an essentially ceremonial purpose can be taken as a measure of the strength of the donor’s commitment to the sacrament. The wide-spread use of silver communion vessels, with donors’ engraved names, was not only a remembrance of the donor but also a tangible sign that suggests the donor’s likely devotion to the sacrament. [And for those who were small farmers, the silver vessel may have been their only silver object.

The plates used to hold communion bread, on the other hand, were typically made of pewter rather than silver. We have three communion plates made of English pewter, dating from 1709. At the time, pewter plates were considered a precious possession and were engraved with initials and stamped with coats of arts, and polished with as much care as were silver vessels.

The letters on our pewter plates are almost worn through with polishing. In 1831, we acquired the two silver communion plates. They were the last silver gifted to the church.

Before turning to the stories of our individual donors, it should be noted that the church silver was used for multiple purposes in addition to communion – vestry meetings, local festivities, opening of new meeting houses, and funerals. And the wine did pour. This seems to contrast with our impression of the Puritans as being rather dour and prim. For example, mourners at the funeral of Mary Norton, widow of John Norton, minister of the First Church of Boston, consumed over 51 gallons of the best Malaga wine….The custom came to an end in 1742, when the General Court of Massachusetts forbade the use of wine and rum at funerals.

Who Were The Donors?

Eight people gave a total of nine pieces of silver to the Second Parish Church. Three of them were women – all named Sarah. Five made gifts during their lifetimes, while three made bequests. The church decided to purchase four additional pieces, all funded by church members.

I’ll talk about the donors and their silver in chronological order. In this way, I can trace their lives and take us through the familiar timeline up to and through the American Revolution.

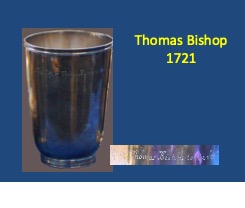

Thomas Bishop

The first silver given to the Second Parish of Roxbury was a beaker by Thomas Bishop in 1721, nine years after the church was founded. He was 75 years old. His life reflects the earlier days of Puritan New England – that is, the mid to late 1600s. Born in Ipswich in 1646, he was apparently a merchant trading in the West Indies (Barbados) for about 10 years before serving as a soldier in King Phillips War (1674-75). He settled in Roxbury after the war, when he was about 30. He was a “husbandman” – that is, a small farmer. In 1670, he had sold land bequeathed to him by his father, and later received 30 acres of land in Roxbury. He also held various town office roles that male landowners voluntarily undertook, offices that were decided in the annual general meeting of the inhabitants of Roxbury. He was variously Surveyor, 1677; Constable 1678/1680; Tythingman, 1683, Fence Viewer, 1688; Haward or Field Driver, 1693; Tythingman, 1698; Fence Viewer 1704, and Surveyor, 1708.

The roles reflected what was important to the community at the time – surveying additional plots of land within Roxbury as instructed by the General Court, ensuring that fences/stone walls were within proper boundary lines, ensuring that domestic animals were under control in the commons, AND making sure residents attended and stayed awake in church (tythingman). In addition to keeping the boys under control, he reported whether all members attended public worship. What I find especially interesting about some town offices is that they existed because undesirable things did happen. Fences did cross boundary lines, domestic animals did get loose and graze in others’ pastures, and people did fall asleep in church. These town offices were local — in service to this rural community. Bishop and other Roxbury donors of silver were typically not the upper class politically – they were not the selectmen, town treasurer, or representatives to the General Court.

Bishop’s personal life reflects the difficulties and tragedies of domestic life, especially for married women. Thomas Bishop was married at least four times, widowed three, with his first two wives dying in childbirth with their first child. The terse language in the First Parish records is sobering:

August 3, 1680, Thomas, son of Thomas Bishop baptized.

August 8, 1680, Sister Bishop, “a godly prudent woman” buryed.

Then again, 14 months later:

October 4, 1681, Elizabeth, wife of Tho. Bishop buryed.

Elizabeth died in childbirth, but a baby girl (also named Elizabeth) survived, although there is no record of her baptism.

Two years later, on 7 June 1683, Thomas Bishop married the widow Ann Douglas Gary, also of Roxbury. The widow Gary had lost her 46-year old husband Nathaniel and infant daughter Dorcas to small pox in 1678, in a three-month period when 20 people from the First Parish of Roxbury died of the pox. Widow Gary was 11 years older than Bishop. When she married him, she had 8 surviving children, ranging in age from 7 to 22. She died in 1691 in her mid-50s.

Bishop’s domestic life illustrates that the economic unit of the early colonies was a husband and wife and their children working a self-sufficient farm. People married, and if they were widowed, they remarried quickly. By the time Thomas Bishop was 45 years old, he had been married and widowed three times. With high death rates – from accidents, pox, war, and childbirth — multiple marriages were the norm as were numerous children.

Thomas Bishop died in 1727 at age 82. He was survived by his wife, Lydia, (his fourth wife?). His will mentions three sons-in-law and his daughter, Elizabeth, so he had three more daughters. He was buried in the “Berry Ground” of the meeting house, now the Peter’s Hill section of the Arboretum. His grave stone is about 100 yards from my house.

Sarah Townsend Thayer

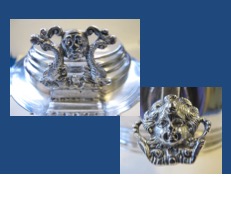

The first tankard was given to the church by Sarah Townsend Thayer, wife of the first minister of the Second Church, Rev. Ebenezer Thayer. It is the oldest and most valuable tankard in our collection. The tankard is easy to recognize – it’s the only flat topped one in the set. It also has a cherub at the top and one on the base of the handle. It was crafted in 1713, most likely as a wedding present as her initials are on the bottom. She gave it to the church in 1732, the year before she died.

Sarah’s adult life reflects the first third of the 1700s. Sarah Townsend Thayer was born in Boston on September 14, 1680, the eldest daughter of Penn Townsend and Sarah Addington. She was born into an extraordinarily well-connected and well-educated political family.

Her father, Penn Townsend, was a prominent Boston civic leader. He was a colonel in the Boston militia, a Justice of the Peace, a Boston Selectman, and Chief Justice of the Superior Court for Suffolk County. He went on several diplomatic missions at the request of the Governor – one to join other delegates from New York, New Jersey, Connecticut and the Five Nations to reaffirm their alliance against Canada (1694), another (1704) to negotiate with the Indians at Albany, NY. He was also an Overseer of Harvard College for almost 20 years (1708-1727).

Sarah’s mother’s family was equally well connected politically. Her mother, Sarah Addington, was the sister of Issac Addington, the Speaker of the House of Representatives and Judge of the Court of Common Pleas. Her maternal grandmother (Anne Leverett) was a sister of Governor John Leverett.

Especially because she was the eldest daughter, we can assume that she was exposed to this political world at an early age and was expected to navigate within it. She was also probably very well educated. Women in the Townsend family were well-read; her aunt, Deborah Townsend Thayer, taught school for a while after her husband died. Also, in Sarah’s will, her library was valued at 140 pounds – a tidy sum for that time.

Because of the untimely death of Sarah’s mother (when Sarah was 12) and of her first step-mother (when Sarah was 19), Sarah probably served as mistress of the house, especially when she was in her 20’s (the first decade of the 1700s). Her father did not remarry (for the third time) until Sarah was 30, unmarried and most likely living at home. She was seen as one of the “good catches of the day,” and married Ebenezer Thayer on 2 July 1713 when she was 33.

She would have known Ebenezer Thayer, the first minister, because they were first cousins, and both grew up in Boston. They married in 1713, the year after he became minister of the Second Parish. Thayer was probably the most well-educated man in Roxbury. He had received both a BA and MA from Harvard and also served as Scholar of the House after he graduated. Samuel Sewell, again in his diary, wrote that Thayer was “heard to very good content” and elsewhere was called “a very valuable Minister in the Neighborhood.” He was invited to give sermons outside the church, and throughout his ministry (1712 – 1733) he served on the Board of Overseers of Harvard College, as did the ministers of the six adjoining towns.

It was Ebenezer Thayer’s good fortune to marry Sarah Townsend as ministers were notoriously low-paid and Ebenezer was a man of moderate means. Other than firewood, left- over coin, and the parsonage, ministers were often left to their own devices. The parsonage, by the way, was located at the corner of what we now call South and Walter Streets, where a market is located today. Sarah and Ebenezer lived in the parsonage for 20 years, until her death on 8 February 1733 and his death less than a month later (6 March 1733). She left an estate valued at “nearly 1740 pounds, including a negro worth 95 pounds, plate to the value of 137 pounds, and a library inventoried at 140 pounds.” It was a considerable fortune.

After Sarah gave the tankard to the Second Church in 1732, there was a hiatus of 30 years before the church acquired other silver – and then it came in a rush.

Scarbrough, Payson, and Church Members

Three tankards were added to the silver service in 1761 and 1762, two from donors (Sarah Scarbrough in the center and Col. Benjamin Payson on the right) and one through subscription (on the left), the first time that funds for silver were solicited from the congregation.

The addition of these silver tankards reflected the growing population of the community as well as its growing prosperity. These were the first contributions from the descendants of the original Roxbury immigrants — unlike Thomas Bishop and Sarah Thayer who had moved to Roxbury as adults. Benjamin Payson, for example, was the grandson of Mary Eliot, sister of John Eliot, teacher and minister of the First Parish church, our parent church. Sarah Mayo Scarbrough came from a birth family of some means– the Mayo family. Her father, Thomas Mayo (13 November 1673 – 26 May 1750) was a farmer and manufacturer of potash (used in fertilizer) and owned land in Oxford and Warwick, MA, given him for military service. Because of her family’s wealth, she would have had money of her own. We don’t know why she gave a tankard to the church, although like Sarah Thayer, she had no children.

It’s very difficult to trace the lives of women in colonial times – the genealogies are usually patrilineal, following fathers and sons. We do know that women did own property— in the 1771 tax valuation, 327 persons owned property in Roxbury, including 15 women. Like Sarah Townsend Thayer, women could make wills and bequeath goods independent of their husbands.

The 1760s were a bustling time. The congregation had grown, and the families living in Jamaica Plain were actively discussing having a church of their own – The Third Parish Church of Roxbury. By this time, the original meeting house was 50 years old and in great need of repair. There was talk as well of building a new meeting house. By 1769, the Jamaica Plain church was formed and officially recognized four years later. By 1773, the Second Parish Church had moved to a new site and erected a new building as well.

Samuel Griffin

In 1770 Samuel Griffin, another grandson of Great Migration immigrants, bequeathed a tankard to the church – making it now five tankards. He was 76 years old. His father, Joseph Griffin (bap. 17 May 1657 – 17 February 1714), was one of the 17 signers of the first covenant for the Second Church of Roxbury (2 November 1712). Samuel held various town offices (fence viewer (1723-24) and tythingman (1728-29)), as had his father before him.

John Mory

In 1774, the church was gifted its silver baptismal basin by John Mory. He was the grandson of Thomas Morey, one of the signers of the April 1711 “humble address” praying pardon from the General Court after Roxbury residents created the Second Parish church without Court permission – part of the “act now, apologize later” philosophy. For nearly a century, the Moreys owned a large tract of land on both sides of Centre Street in Jamaica Plain. Like other male landowners, they had held various town offices — fence viewer, constable, surveyor, tythingman – each for a year. John Mory gave the church the baptismal basin as a gift, not as a bequest or a “no strings attached” financial contribution. I don’t have any evidence about WHY he gave the basin, but I have a hypothesis. In going back through the genealogy, I found that while his grandfather Thomas had nine children, only one male lived into his mid-20s – the father John. The father John in turn had five children, and only one male child, our donor John. In March 1774, after one son (1769) and one daughter (1771) were born, John’s wife (Mary Cheney) had their second son (Ebenezer Cheney Morey). My hunch is that he gave the basin to celebrate the birth of his son.

This was the last gift of silver to the church before the Revolution. It would be another 30 years before the church acquired its next piece of silver – the sixth and final tankard.

The Years of the Revolution

The Revolution impoverished communities. Each precinct or parish had a quota of soldiers to furnish to the Continental Army, along with the funds to outfit and support them. In 1778, for example, the Second Parish church “voted to raise £500 to incourage [sic] the raising of men that are now called for in this precinct.” According to Seaver, these sums were frequently raised during the war for paying the men engaged. The largest sum raised was £10,000 but, as Seaver noted, this was depreciated currency. Substantial debts were accrued, and many communities were in debt after the Revolution was over.

The First Parish Church of Roxbury being so much closer to Boston harbor (located not far from Roxbury Crossing) was particularly hard hit. During the siege of Boston (1775-76), the meeting house of the First Parish was occupied by American troops. The records of the First Church of Roxbury noted: “It was a constant and conspicuous target for the British cannon.”

Closer to home, troops from Rhode Island and Connecticut were stationed in Jamaica Plain. Although the Second Parish Church was located further from the fighting, the Dedham Road was the lifeline of the Army, connecting the active forces with their arms and supplies stored in Dedham. It would have also been the retreat route for the Continental Army had Washington been unsuccessful. “Walter’s Meeting House” (that is, the meeting house of the South Parish church) is highlighted along the Dedham Road route of the 1775 map that George Washington used.

At the time of the Revolution, most Roxbury residents supported independence from the crown. They were third or fourth generation colonists. Most were small farmers and few would have travelled to or from England in prior generations. Most were likely concerned with the crown’s rising taxes and tariffs. In fact, in April 1775, Roxbury mustered three companies of Minute Men (150 men) who were sent to Lexington. Families of the silver donors of the 1760s were represented among the Minute Men and served in the Continental Army. Sarah Mayo Scarbrough’s two younger brothers (Captain Thomas Mayo and Major Joseph Mayo) and six of her nephews fought in the Revolution. One brother (Major Joseph Mayo) and two of her nephews were killed (Lt. John Mayo and Private Samuel Mayo). Two of Colonel Benjamin Payson’s grandsons were Minute Men as well (Corporal Payson Williams and Private Thomas Williams).

The adversity of the Revolution seems to have found its way into the communion service of the Second Parish. Church files noted in 1776: “After Lecture, etc., as it had been the practice here for many years after the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper was administered for the remainder of the wine to be used by any person then present and as it encouraged no good end and as the article was scarce and dear, the Church voted that no more wine should be given away after sacrament.”

Samuel Cookson

In 1806, the sixth and final tankard was bequeathed by Samuel Cookson, “as a token of my regard” for the church. The tankard is domestic silver, having been in private hands for more than 50 years. Four years earlier (1802), he had given the church a clock. We still use the clock; it’s on the rear wall of the sanctuary.

Cookson became a member of the Second Church in Roxbury in 1795, when he was 51, moving here from Boston. He was a shop keeper of some means, with his store at the corner of Walter and South Streets, where the parsonage had once stood and where another market stands now. During its day, though, it was known as “Cookson’s Corner.”

While an upstanding citizen and successful businessman, Samuel Cookson had a difficult childhood in Boston. His father, Obediah Cookson, was a wholesale and retail grocer at his shop, Cross Pistols (his father John was a gunsmith) on Fish Street in the North End. He was “a Person thought to be of unsound mind.” Obediah tried to sell a house on Long Wharf that he did not own. On another occasion, Boston fire wardens had to come to his shop to remove six barrels of gunpowder he had decided to store there. His wife, Faith Waldo, left him in 1748, taking her two small children (Samuel was 4) with her. Obadiah then wrote a scathing denunciation of her in a newspaper advertisement. The newspaper later retracted the advertisement when it found the allegations were false. Samuel was later raised by his mother and maternal uncle, Thomas Waldo. My sense is that Samuel had very warm feelings toward his two maternal uncles as he named his sons after them.

Cookson did not fare particularly well with his first father-in-law either. In 1769, when Samuel was 25, he married Mary Church at the Hollis Street Church in Boston. She was the daughter of the talented physician and skillful surgeon, Dr. Benjamin Church. Dr. Church was also active in Boston’s Sons of Liberty movement. Unfortunately in July 1775 (during the Siege of Boston), Dr. Church sent secret information to the British commander, General Thomas Gage, and pledged his loyalty to the Crown. He was convicted of “communicating with the enemy” and imprisoned as a spy. He was released in 1778, and left Boston on a schooner to the Caribbean that never arrived. Cookson stayed in Boston. He and Mary had three sons. In 1793, sometime after his first wife died, he married the widow Susannah Osborne of Roxbury, and moved here two years later (1795). His ten years as a shopkeeper in Roxbury, until his death in 1806, must have seemed calm by comparison to his earlier life.

We have now made the rounds of our original slide – the church silver of one beaker, six tankards, and a baptismal basin. But this time we can say who gave them.

Sarah Townsend Thayer’s tankard, Thomas Bishop’s beaker,

and Colonel Benjamin Payson’s tankard.

What can we say about the quality of our silver? Who were the silversmiths? How do they stack up against the others of their time?

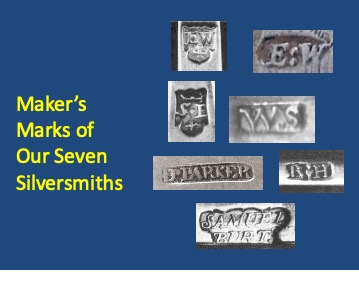

Who Were the Silversmiths?

Second from top row: Samuel Edwards and William Simpkins. Third from top row: Daniel Parker and Benjamin Hurd. Bottom row: Samuel Burt

We have identified seven silversmiths in our collection. Silversmithing was often a family business, with sons apprenticed to fathers, typically for seven years. Of the six Boston silversmiths, five came from silversmithing families, while another apprenticed with one of them. Here are the maker’s marks of our seven silversmiths.

The earliest works in our collection were crafted by Edward Webb (1666-1718) and Edward Winslow. Webb was the most prolific of the immigrant goldsmiths who entered Boston. Although he trained in one of London’s most sophisticated shops, all of but one example of his silver is plain, like his Thayer tankard (the one with the two cherubs). All of our other silversmiths were born and apprenticed in Boston, with Winslow among the most famous. He crafted the silver beaker, the first silver piece in our collection. Most of his work was completed before 1720, as he became more politically active, first as sheriff of Suffolk County (1716-1743) and then as judge (1743 until his death in 1753 at 85). He was also the great grandson of Anne Hutchinson, famous “heretic” of the 1630s who was banned from the Massachusetts Bay Colony for her beliefs.

Paul Revere may have been the most famous of Boston silversmiths, but according to Janine Skerry, Silver Curator at Colonial Williamsburg, the Burt and Hurd families “… were all outstanding craftsmen.” In our collection, Samuel Burt made a tankard, while Benjamin Hurd made the baptismal basin. Other tankard makers, Samuel Edwards and William Simpkins, also came from families of silversmiths. Samuel Edwards was the master silversmith for Daniel Parker, a fellow member of Sons of Liberty with Paul Revere. Some of Parker’s work is in the Colonial Williamsburg collection.

In short, our silver was made by outstanding craftsmen and reflects the functional simplicity of the domestic silver of the time.

What about the later silver?

In 1819 and 1827, three wine cups were acquired by the church through subscription. There are no named donors and no maker’s marks so we don’t know who the silversmiths were. The last silver pieces are two silver communion plates, given to the church by Mrs. Sarah Corey, also with no maker’s marks. Our church is located on the corner of Centre and Corey Streets, with Corey Street itself named after Deacon Ebenezer Corey. Sarah remains a mystery at the moment. We’ll have to stay tuned for Sarah.

Questions?

Before opening up for questions, I want to thank the people who helped make the presentation possible:

Julie McVay, our church historian.

Steve Greene and Karen Bishop. Steve and Karen did the photo shoot at the MFA with me.

Kelly L’Ecuyer, Ellyn McColgan Curator of Decorative Arts and Sculpture, Museum of Fine Arts.

Alexander Goriansky, silver appraiser who appraised our silver in 2008.

Judy Neiswander, former decorative arts curator.

Lastly, we have made arrangements with the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through Kelly L’Ecuyer, to have two pieces of our silver (the Thayer tankard and the Mory baptismal basin) on display in their own display case in the new Art of the Americas wing, starting May 14,2012. Do stop by and see them. It’s the first time they’ve been on public display since 1911.

Exhibit 1. Silver Collection of the Second Parish Church of Roxbury (Now The Theodore Parker Unitarian Universalist Church), 2012

| Object | Donor | Maker | Date Made/Date Given to Church |

| Three pewter plates | BS, HW, MB | Spackman & Grant London | 1709/DK |

| Beaker | Thomas Bishop | Edward Winslow (1669-1753) | 1721 |

| Tankard | Sarah Thayer | Edward Webb (1666-1718) | 1713/1732 |

| Tankard | Benjamin Payson | Samuel Edwards(1705-1762) | 1761 |

| Tankard | Subscription | William Simpkins (1704-1780) | 1761 |

| Tankard | Sarah Scarbrough | No maker’s mark, bottom may have been replaced? | 1762 |

| Tankard | Samuel Griffin | Daniel Parker (1727-1785) | 1770 |

| Baptismal Basin | John Morey | Benjamin Hurd (1739-1781) | 1774 |

| Tankard | Samuel Cookson | Samuel Burt (1724-1754) | c1750/1806 |

| Three Wine Cups | Subscription | No maker’s mark | 1819 and 1827 |

| Two silver plates | Mrs Sarah Corey | No maker’s mark | 1831 |

Note: If only one date given, then silver was given to the church the year it was made. We have no information on when the pewter plates were given to the church. The silver is stored at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts.

Notes

Silver Stories was an invited address to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the gathering of the Theodore Parker Unitarian Universalist Church, West Roxbury, MA. Delivered May 6, 2012. A member of the congregation, Mary Ann Millsap is the church liaison for restoration and heads the capital campaign. She has a Master of Arts degree in sociology from Cornell University and a doctorate in education from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education.

Why Silver?

- The full description of the silver, including height, weight, and engraving, is contained in Jones, E. Alfred. The Old Silver of American Churches. Letchworth, England: National Society of Colonial Dames of America, 1913. All information on silversmiths, their work, and maker’s marks is contained in Kane, Patricia E. Colonial Massachusetts Silversmiths and Jewelers. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1998. It includes all but one of the 18th century pieces in our collection. Additional information on Benjamin Hurd is contained in French, Hollis. Jacob Hurd and His Sons Nathaniel and Benjamin Silversmiths 1702-1781. Riverside Press [Cambridge] for The Walpole Society, 1939.

- R.T. Haines Halsey is quoted in the New York Times, “Historic American Silverware Soon to be Exhibited: Rare Specimens of 17th and 18th Century Plate from Many States at the Metropolitan Museum.” September 24, 1911.

Who Were These People? Where Did They Come From? The Great Migration

- For information about the Great Migration, including John Eliot and his congregation, see Thompson, Roger. Mobility and Migration: East Anglian Founders of New England, 1629-1640. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994.

- The quotation by Francis S. Drake appeared in Early Families of Roxbury, Massachusetts. www.geni.com/projects/Early-Families-of-Roxbury-Massachusetts. No date.

What Did They Create? What Were Their Church Practices?

- Most of the general information on Puritan church practices comes from Earle, Alice Morse. The Sabbath in Puritan New England, Seventh Edition. First edition was published in 1891, available through the Gutenberg Books project at www.gutenberg.org.

- Requirements of the General Court of Massachusetts were found in Ernst, Ellen Lunt Frothingham, The First Congregational Society of Jamaica Plain, 1769-1909, 1909.

- Information about Roxbury, Massachusetts, was found in Drake, Francis. S. Thirty-Fourth Report Boston Records, The Town of Roxbury, Registry Department of the City of Boston, Document 93, 1905.

- Information about the Second Parish Church was found in church records that had been summarized by Charles M. Seaver. A Short History of Our Church, First Parish, West Roxbury, Formerly Second Church of Christ Roxbury. Text from files at West Roxbury Historical Society, “Church: First Parish 1632-1966, File 1 of 2. Page 3 of typed version. No date. Additional information was found in Lehmer, Mary. “The Walter Street “Berrying” Ground. Arnoldia, Volume 21, Number 12, October 27, 1961.

- For more information about the 1600s, see Philbrick, Nathaniel. Mayflower. New York: Penquin Books, 2006, and LaPlante, Eva. American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the Puritans. New York: HarperOne, 2005.

- Slavery is an underexplored topic in Puritan New England. At least three members of the Second Parish church owned slaves, including the wife of the first minister, the second minister, and the donor of the baptismal basin. Some detail is provided in Roxbury during the Siege of Boston, April 1775-March 1776. Historic Roxbury/Boston National Historic Park. No date.

Celebrating the Sacraments

- For the form and uses of different communion vessels, see Ward, Barbara McLean. In a Feasting Posture. Communion Vessels and Community Values in Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century New England. Winterthur Portfolio, Volume 23, Number 1, Spring 1988.

- For a discussion of the importance of silver in communion services, see Peterson, Mark A. Puritanism and Refinement in Early New England: Reflections on Communion Silver. The William and Mary Quarterly. Third Series, Volume 58, Number 2, April 2001.

- For the multiple uses of communion silver, see Jones, E. Alfred. The Old Silver of American Churches. Letchworth, England: National Society of Colonial Dames of America, 1913.

The Donors:

Thomas Bishop

- In Ipswich Deeds (5:57), Bishop is referred to as “late of Barbados.”

- Holders of various town offices are described in Dunkle, Robert J. and Anne S. Lainhart. Town Records of Roxbury, 1647-1730. New England Historical Genealogical Society, 1997.

- Land records for Roxbury and Church records of the First Parish Church of Roxbury are found in the Sixth Report of the Record Commissioners Roxbury Land and Church Records. Second Edition. Boston: Rockwell and Church, City Printers, 1884.

- Information on the Gary family is also found in Brainard, Lawrence. The Descendants of Arthur Gary of Roxbury, Massachusetts. Boston, MA: 1981.

- Information on New England marriages is found in Torrey, Clarence Almon. New England Marriages Prior to 1700. Baltimore: Baltimore Genealogical Publishing Company, 1985.

- In his November 4, 1981, memo to the Theodore Parker Church, the late Rev. Robert Haney (minister of the church at that time) cites information from Thomas Bishop’s will, including his role as husbandman.

Sarah Townsend Thayer

- Several sources were cited on the web for Penn Townsend and/or Sarah Addington. They included: Savage, James. Genealogical Dictionary of the Early Settlers of New England. Also, “Notes on the Addington Family” NEHGS Register. Volume 4. And Addingtons of the United States by Addington, David Vern and George H. Bull, 1998.

- Among the documents I reviewed on the web were: Funeral Sermon for Honorable Penn Townsend, Esq. by Thomas Foxcroft, M.A., Pastor of the Old Church in Boston, 1727; First Church (Boston) Penn Scholarship Disbursement Records, 1717-1819: an Inventory. Harvard University Archives, call number HUC 1680.2; Harvard University List of Overseers; and Papers of John Leverett, 1662-1724, in Harvard University Library.

- Most information on Ebenezer Thayer comes from Clifford K. Shipton, Sibley’s Harvard Graduates, Volume V. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1937, pp 456-57.

Scarbrough, Payson, and Church Members

- Information on Sarah Scarbrough was referenced in Mayo, Chester Garst. John Mayo of Roxbury, Massachusetts, 1630-1688. A Genealogical and Biographical Record of His Descendants. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1965.

- Information on Benjamin Payson comes in part from Vital Statistics of Roxbury, Massachusetts to the End of the Year 1849. Salem, Massachusetts: Essex Institute, 1925-26, 1:271 and 2:609. Other information was found in genealogies on the web but are not yet verified.

- Information about the Second Parish Church was found in church records that had been summarized by Charles M. Seaver. A Short History of Our Church, First Parish, West Roxbury, Formerly Second Church of Christ Roxbury. Text from files at West Roxbury Historical Society, “Church: First Parish 1632-1966, File 1 of 2. Page 3 of typed version. No date. Additional information on the Second Parish meeting house is found in Lehmer, Mary. The Walter Street “Berrying” Ground. Arnoldia, Volume 21, Number 12, October 27, 1961.

- Information on the Jamaica Plain church was found in Ernst, Ellen Lunt Frothingham. The First Congregational Society of Jamaica Plain, 1769-1909. Published in 1909.

Samuel Griffin

- Information on town offices held by Griffin and his father, Joseph, are found in Dunkle, Robert J. and Ann S. Lainhart, The Town Records of Roxbury, Massachusetts, 1647-1730. Boston: New England Historical Genealogical Society, 1997.

- “A Platform of ye Church Covenant” dated November 2, 1912, is the original covenant of the Second Parish Church, drafted by Rev. Ebenezer Thayer. Joseph Griffin is one of the 17 initial signatories. I have a typed version of the covenant.

John Mory

- The full text of the “humble address” appears in Robert J. Dunkleand Ann S. Lainhard. The Town Records of Roxbury, Massachusetts, 1647-1730. Boston: New England Historical Genealogical Society, 1997. A shorter version of the “humble address” appears in Francis S. Drake. Thirty-fourth Report, Boston Records, The Town of Roxbury, Its Memorable Persons and Places. Boston: Municipal Printing Office, 1905.

- For the Morey family in Jamaica Plain see Jamaica Plain News, May 18, 1907. Address given before the Jamaica Plain Tuesday Club by Mr. Frank E. Bradish called “Stories of Woodland and Pasture and of Life in the Old Days on the Western Hills of Jamaica Plain.”

- Genealogical information was cited in James Savage. Genealogical Dictionary of the First Settlers of New England. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, Inc., Second Edition, 1996. Also in Luther M. Harris. Robert Harris and His Descendants. Boston: Henry W. Dutton & Son, 18961, Reprinted by Higginson Books. Further mention of the family is found in Descendants of Roger Mowry on familytreemaker.geneology.com.

The Years of the Revolution

- That so few colonists returned for visits to England is discussed in Roger Thompson’s Mobility and Migration: East Anglian Founders of New England, 1629-1640. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1994.

- Information about the Second Parish Church was found in church records that had been summarized by Charles M. Seaver. A Short History of Our Church, First Parish, West Roxbury, Formerly Second Church of Christ Roxbury. Text from files at West Roxbury Historical Society, “Church: First Parish 1632-1966, File 1 of 2. Page 3 of typed version. No date.

- Information on the First Parish Church of Roxbury is found in Walter Eliot Thwing. History of the First Church of Roxbury, 1630-1904. Published in 1904.

- Information on the Jamaica Plain church was found in Ernst, Ellen Lunt Frothingham. The First Congregational Society of Jamaica Plain, 1769-1909. Published in 1909.

- Information on Minutemen and soldiers in the Continental Army from Roxbury, see Francis S. Drake. Thirty-fourth Report, Boston Records, The Town of Roxbury, Its Memorable Persons and Places. Boston: Municipal Printing Office, 1905.

Samuel Cookson

- Information on Samuel Cookson’s life is found in Genealogy of the Waldo Family: Descendants of Cornelius Waldo of Ipswich, Massachusetts, as cited on ancestry.com.

- Multiple sources provide information on Obadiah Cookson, Samuel Cookson’s father. An advertisement in the Boston Gazette (June 2, 1737) accused Obadiah of offering to sell a property he did not own. Boston City Document No. 87, March 1740, page 230, describes the removal of the gun powder. In his own advertisement in the Boston Gazette (June 28, 1748) Obadiah accuses his wife who had left him with theft and damages. The Boston Gazette later retracted the advertisement . Citations are found on www.newspaperabstracts.com. Lastly, in Genealogy of the Waldo Family on ancestry.com, a mortgage dated September 1, 1756, cited Obadiah “as thought to be of unsound mind.”

- The marriage of Samuel Cookson and Mary Church is recorded in Boston, Massachusetts, Marriages 1700-1809.

- Cookson’s admission to the Roxbury church is noted in Charles M. Seaver. A Short History of Our Church, First Parish, West Roxbury, Formerly Second Church of Christ Roxbury. Text from files at West Roxbury Historical Society, “Church: First Parish 1632-1966, File 1 of 2. Page 3 of typed version. No date.

Who Were the Silversmiths?

- All information on silversmiths, their work, and maker’s marks is contained in Kane, Patricia E. Colonial Massachusetts Silversmiths and Jewelers. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1998. It includes all but one of the 18th century pieces in our collection. Additional information on Benjamin Hurd is contained in French, Hollis. Jacob Hurd and His Sons Nathaniel and Benjamin Silversmiths 1702-1781. Riverside Press [Cambridge] for The Walpole Society, 1939.

- The interview with Janine Skerry appears in Keane, Maribeth and Brad Quinn. An Interview with Silver Curator and Collector Janine Skerry. Collectors Weekly. March 28, 2010.

What about the later silver?

- The later silver is described in Jones, E. Alfred. The Old Silver of American Churches. Letchworth, England: National Society of Colonial Dames of America, 1913.

Photo Credits

All photos were taken by Steven Greene with the exception of the pewter communion plate (page 5), the silversmith maker’s marks (page 13), and the silver communion plates (page 14) that were taken by Mary Ann Millsap.